Are any worth the effort?

Jacob Schor ND, FABNO

July 22, 2019

When it comes to diet and cancer, we face a conundrum of how best to advise our patients on what to eat, especially those who have already made up their minds about what they believe. Numerous large prospective epidemiological studies have provided convincing evidence that following the basic dietary suggestions from the American Cancer Society and the American Institute of Cancer Research will decrease cancer incidence from 17% to over 50% and decreases cancer-specific mortality by 20% to 30%. [1][2][3][4][5]. Yet despite this compelling evidence nearly half of our cancer patients, or those at high risk of developing cancer, chose to follow some other diet that they believe will provide them with even greater anti-cancer benefits. [6][7][8][9][10]

At this point there is little evidence that adhering to specific diets promoted outside of the general ACS and AICR guidelines convey additional benefit to patients. My routine has been to calculate a Mediterranean diet score and work to improve on it and add on cancer specific goals where appropriate. Devoting time during patient visits to debating the relative merits of their dietary beliefs often feels counterproductive as patients are often adamant in their faith and rationale arguments have little impact. Our goal to improve patient outcome might be better served by encouraging patients to follow those aspects of their chosen diet that are congruent with the dietary guidelines and tactfully lobbying against ideas that directly counter the guidelines. Best that we pick fights that most matter to patient outcome and not sweat the small stuff.

Common diet types we most often encounter patients following include the ketogenic, alkaline, macrobiotic, vegan, and paleo.

Ketogenic Diet:

Ketogenic diets are high-fat, low-carbohydrate, adequate-protein diets. 65% or more of calories come from fat, while carbohydrate intake is restricted to just 20 to 60 grams per day. This ratio of macronutrients forces the body to metabolize lipids rather than carbohydrates or proteins and shifts the body’s primary energy substrate from glucose to ketones.

The ketogenic diet was developed in the 1920s to help control childhood epilepsy. It was already known that these patients often improved when fasting, but chronically starving children was not a suitable long-term strategy. In 1921 R.T. Woodyatt reported that people who consumed too low a proportion of carbohydrate and too high a proportion of fat experienced changes similar to what occurred following a starvation diet, notably the appearance of acetone and beta-hydroxybutyric acid in the blood.[11] R.M. Wilder at the Mayo Clinic tried epileptic children on this ketogenic diet and they experienced benefits similar to what they experienced from fasting. [12]The formula of 1 gram of protein/kilogram bodyweight and 10-15 grams of carbohydrate per day with the remaining calories from fat that is still used today was published in 1925 by M.G. Peterman of the Mayo Clinic. [13] This Peterman diet was the mainstay for treating epilepsy for decades but fell into disuse with the introduction of anti-seizure medications in the 1950s. During the 1970s, Robert Atkins popularized a ketogenic patterned diet for the treatment of obesity. [14] The ketogenic diet was revived for treating epilepsy in the 1990s [15]and has been effective in numerous clinical trials.[16] In recent years, the diet has been promoted as a potential treatment for a wide spectrum of illnesses including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, autism, depression, polycystic ovary syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. [17]It was only a matter of time until the ketogenic diet was suggested as useful in treating cancer [obviously that is a bit opinionated and I will amend it in a second draft].

Some practitioners now suggest following a ketogenic diet should be used as an adjuvant cancer treatment because it selectively kills cancer cells. However, some researchers insist ketogenic diets are highly undesirable because they may trigger and/or exacerbate cachexia development and usually result in significant weight loss.[18]The ketogenic diet has been reported to be helpful against several cancer types when tested in cancer cell cultures and laboratory animals. [19][ibid] The general theory is that this fat-rich, low-carbohydrate diet will reduce glucose levels and induce ketosis so that cancer cells will be starved of energy while normal cells adapt their metabolism to use ketones as an energy source and survive. There are some known exceptions to this idea; for example, some BRAF mutated tumors prefer ketones as their energy source.[20]Many of these cell studies have focused on brain tumors. [21]In a systematic literature review published in 2017 researchers identified 13 animal studies that had looked at the effect of a ketogenic diet and that met their inclusion criteria. Of these, 9 articles suggested that the ketogenic diet “… had a beneficial effect on tumor growth and survival time. Tumor types included pancreatic, prostate, gastric, colon, brain, neuroblastoma and lung cancers.” The authors pointed out that, studies in this area are rare and inconsistent and that because, “… of differences [in] physiology between animals and humans, future studies in cancer patients treated with a [ketogenic diet] are needed.” [22]

Human evidence supporting ketogenic use for cancer is limited to case reports and small open-label studies, that while they confirm the feasibility and safety of ketogenic diets do not inform us about long term benefit. This is a challenging diet to follow and the explanation often given to patients who do not experience benefit is their failure to adhere tightly enough to the diet is to blame. The studies suggest that ketogenic diets are safe, and do not negatively impact quality of life in the short term.

The evidence in support of following a ketogenic diet would be compelling if our patients were all mice. At this point the evidence to use this diet to treat people remains tentative. We will hope that in the future some clarity and consistency emerges.

Alkaline Diet:

Proponents of the alkaline diet believe that most cancers are caused by an acidic environment in the body and that the primary cause of this acidosis is acid-forming foods. The Western diet is characterized by high intake of animal products and refined carbohydrates, with limited consumption of fruit and vegetables, and is thus considered to be highly acid-forming.

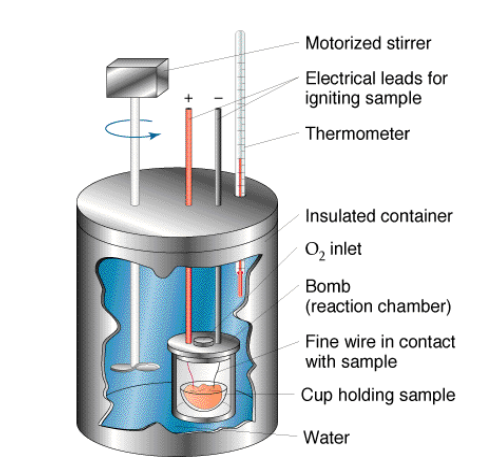

We need to go all the way back to Marcellin Berthelot (1827 – 1907) to understand the origin of the acid and alkaline diet concept. Berthelot was a French chemist, famous for the study of thermochemistry. In his 1879 book Mecanique Chimique, which introduced the concepts of ‘endothermic’ and ‘exothermic’ reactions, he described a laboratory apparatus he had invented for his experiments, an apparatus he called a bomb calorimeter.

A bomb calorimeter consists of a chamber pressurized with oxygen and suspended in a water bath. A sample is added to the chamber and once everything is sealed, ignited. The pressurized oxygen guarantees that whatever was inside the bomb rapidly incinerates and is reduced to ash. The heat released by this controlled explosion is absorbed by the water bath and the water’s temperature increase is equivalent to the calories of heat given off by the sample. This is how a food’s calorie content is determined to this day.

After the experiment is done, all that is left inside the bomb calorimeter is ash. If one adds water to this leftover ash, one can measure its pH and tell whether it is acidic or alkaline. This measurement is the basis of describing some foods as alkaline or acidic. In 1912, Sherman and Gettler published a paper that listed foods that had been tested in this manner, classifying them as acidic or alkaline foods based on the pH of their leftover ‘bomb ash.’[23]

The current alkaline-ash diet is based on this once upon a time experiment. This is not cutting-edge science. In general, fruits and vegetables leave an alkaline ash, and meats and grains leave acidic ash.

There is a widespread belief that following an alkalinizing diet, that is avoiding foods that produce acidic ash and choosing to eat foods that leave an alkaline ash, is a valid treatment for cancer.

Dr. Neil McKinney, who teaches naturopathic oncology at Boucher Institute of Naturopathic Medicine and author of (book title) thinks poorly of this theory. “To put it bluntly, suggesting cancer can be treated or cured by alkalinizing the body is pure rubbish. Treatments based on alkalizing are quackery.”

McKinney tells me that this fallacy began with Otto Warburg, whose research on the biochemistry of sugar metabolism in the 1920’s to 1940’s won him a Nobel Prize. Warburg found that cancer cells often live in hypoxic, very low oxygen, and acidic conditions and that they derive energy from sugars by fermenting them the way yeast do. He came up with a theory that these low oxygen and high acidic conditions were the cause of cancer.

“Cancer, above all other diseases, has countless secondary causes. But, even for cancer, there is only one prime cause. Summarized in a few words, the prime cause of cancer is the replacement of the respiration of oxygen in normal body cells by a fermentation of sugar.”

— Dr. Otto H. Warburg

Current science explains this phenomenon differently. For a tumor to survive it needs to stimulate the growth of blood vessels. Otherwise, it can’t get all the oxygen it needs to metabolize sugar. Tumor cells stimulate blood vessel growth by producing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Even with this stimulation, tumor cells often outpace the growth of new blood vessels. When they do so, they don’t have enough oxygen.

When oxygen is deficient, tumors change how their cells metabolize sugar. They start breaking it down through fermentation. This isn’t ideal; fermentation releases only about 5% of the energy that would have been produced if oxygen were available. The tumor cells do this to survive, not because they like to. Fermentation of sugar without adequate oxygen produces lactic acid. This is because not only aren’t there enough blood vessels to bring oxygen to the tumor cells, there are also not enough blood vessels to remove waste products like lactic acid. This was a good theory a hundred years ago.

Currently, tumor cell proton pumps get credit for creating the acidic tumor environment. Low oxygen and acidic tissue environments are no longer considered the cause of cancer but instead it is the other way around. Cancer cells create an environment that is acidic and short of oxygen. [24]

The idea persists nevertheless that neutralizing the acid produced by tumors and bringing oxygen to tumor cells can cure cancer. Changing the pH of a tumor does not change its growth rate significantly, nor does it seem to lead to cell death. In 2004, Wenzel and Daniel published results of several experiments using quercetin and other flavones that trigger apoptosis (cellular suicide) in cancer cells. They found that apoptosis occurred independent of changes in alkalinity or acidity of the cellular environment; altering pH did not appreciably effect survival or death of cancer cells. [25]

Even if it were true that raising the pH of a tumor was a useful therapy, there is no easy way to make this happen. The body holds the pH in blood and body fluids within a narrow range. Even a slight shift in pH would change the way enzymes act and the body does everything it can to prevent this from happening. Mechanisms in the body actively buffer any attempt at raising or lowering the body’s pH.

Dr. McKinney writes, “I worked for years in radiation therapy research on the hypoxic cell problem. Cancer does not ever form due to an acidic or a low oxygen environment – rather, advanced tumors create these conditions as they outstrip their angiogenesis capacity. It is not possible to alkalize tumors by any oral supplement, … even IV bicarb will not harm tumors.”

The idea that oxygen will kill cancer cells is equally absurd. Cancer cells love oxygen; lack of oxygen slows their growth. Remember those angiotensin inhibitor drugs, bevacizumab (Avastin) is a prime example; by preventing the growth of new blood vessels to tumors, they suffocate the cancer cells. But let’s stick with this alkaline and acid pH business.

This misplaced and outdated desire to increase the cancer’s pH has gotten cobbled together with the even older old bomb calorimeter ash data. Books and especially websites urge cancer patients to eat alkaline ash producing foods on the theory that this will neutralize the acidic environment that created cancer.

Warburg’s theory was interesting 100 years ago. The belief in this dietary approach is widespread and deeply held by many people and practitioners. Yet if we look for compelling research that might confirm the benefits of following this alkaline diet we come up with slim pickings.

T. R. Fenton has led several systematic review and meta-analysis studies that have examined alkaline diet research. The first was published in 2009 and looked at impact on osteoporosis. It has long been suggested by proponents that eating highly acidic ash foods would rob the body of calcium and lead to bone loss. Fenton’s conclusion after conducting a meta-analysis of all published data did not support this use: “Promotion of the “alkaline diet” to prevent calcium loss is not justified.”[26]

Fenton conducted a second meta-analysis published in 2011 and came to the same conclusion that any suggested association between eating a diet high in acid ash foods and osteoporosis is not supported “…and there is no evidence that an alkaline diet is protective of bone health.”[27]

A systematic review published in 2016 that examined alkaline and acid diets in relation to cancer risk found that “… there is almost no actual research to either support or disprove these ideas.

This systematic review of the literature revealed a lack of evidence for or against diet acid load and/or alkaline water for the initiation or treatment of cancer. Promotion of alkaline diet …. to the public for cancer prevention or treatment is not justified.”[28]

I hesitate to say anything negative to patients about this diet. That’s because fruits and vegetables top the list of foods that burn down to alkaline ash. When people follow this diet. they seem to approximate the general recommendations made by the ACS and AICR of eating more vegetables and fruits and decreasing consumption of animal proteins. Meat and grains top the list of acid producing foods. Reducing consumption of either is in line with modern dietary recommendations. The theory behind this whole business may be nonsense but the results are good. Getting someone to eat more alkaline foods is equivalent to telling them to comply with AICR guidelines that are proven to prevent and fight cancer. Telling someone to avoid eating foods that produce acidic ash is telling them to avoid foods, in particular meat and grains, that increase the risk of cancer. These outcomes may have nothing to do with pH; they have everything to do with the other nutrients present in the foods.

Which leaves us with an ethical question: Should we let people believe in outdated science for the purpose of getting them to do something that is good for them? Do we let our patients follow these alkaline food lists, knowing that the theory that supports their diet is malarkey?

Somedays working with patients is like parenting a three-year old, we have to pick our battles and fighting this one just might not be worth the effort. I confess, to sometimes letting the truth slide and leaving people believing something I know is false but knowing that this crazy idea is inspiring them to eat a healthier diet. Am I wrong to do this?

One last study that needs mention. The most recent study to report on this acid -alkaline concept was published in April 2019. It examined risk of breast cancer in relation to acid load from diet. Women in the upper quartile of dietary acid load had a 21% greater risk of breast cancer than those in the lowest quartile. The association was greater for ER negative tumors, increasing to a 67% greater risk, and more than double the risk for TNBC. [29]

Macrobiotic Diet

The term Macrobiotic originated with Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland (1762-1836) a prominent German physician and a close friend and contemporary of Samuel Hahnemann who wrote a book,Macrobiotics: The Art of Prolonging Life, published in German in 1796 and English in 1797.[30] Macrobiotics and the Macrobiotic Diet as we now use the term is a philosophical approach to life popularized by Japanese philosopher George Ohsawa (1893 –1966)and his students, particularly, Michio Kushi.[31]The diet they promote is predominantly vegetarian and emphasizes natural, minimally processed foods. This diet has been recommended by followers for treating a range of chronic diseases. [32][33] The way macrobiotic followers describe their practice and the role it takes in their lives might be best described as all encompassing.

Kushi described this role,

“I realized that it was essential to recover genuine food, largely of natural, organic quality, and make it available to every family at reasonable cost. Only then could consciousness be transformed and world peace achieved….. ‘macrobiotics’ in its original meaning, as the universal way of health and longevity which encompasses the largest possible view not only of diet but also of all dimensions of human life, natural order, and cosmic evolution. Macrobiotics embraces behavior, thought, breathing, exercise, relationships, customs, cultures, ideas, and consciousness, as well as individual and collective lifestyles found throughout the world.

“In this sense, macrobiotics is not simply or mainly a diet. Macrobiotics is the universal way of life with which humanity has developed biologically, psychologically, and spiritually and with which we will maintain our health, freedom, and happiness.” [34]

In the past few decades macrobiotics has become known in the U.S. as an alternative cancer treatment, so much so that it is referred to as the “anti-cancer diet” and assumed to be effective. Starting in the 1970s and continuing into the early 1990s a series of popular books promoted the diet and included case histories of cancer patients who responded favorably, in some cases near miraculously.

These reports stood in stark contrast to the orthodox opinions from the medical authorities. In the early 1970s, both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Cancer Society (ACS) issued stern warnings against the diet.[41] By 1971 the American Medical Association had condemned macrobiotics, labeling it “a major public health problem.” that posed “not only serious hazards to the health of the individual but even to life itself.” [42] An opinion piece published in JAMA in 1971 summed up the medical consensus of the time, “The Macrobiotic diet represents an extreme example of a general trend toward natural and organic foods. One of the reasons given for the popularity of these unusual diets is that they are considered to be a means of creating a spiritual awakening or rebirth. Some persons have undertaken these diets as a form of protest against the establishment which, in their minds, is represented by the food industry, or even as a means of protest against war or man’s inhumanity to man.” [43]

This condemnation does not seem to have slowed the belief in the anti-cancer diet one iota; if anything, it made the diet more popular.

By 1990, The Office of Technology Assessment’s publication, Unconventional Cancer Treatments, listed macrobiotic diet, along with the Gerson Treatment and Kelley Regimens, as a common dietary approach to the treatment of cancer [44].

By 1984, when B. Cassileth’s landmark study “Contemporary unorthodox treatments in cancer medicine” in which patients and practitioners engaged in alternative cancer care were interviewed,the macrobiotic diet was one of the most popular alternative approaches used by people with cancer.[45]

In Michael Lerner’s 1994 book, Choices in Healing: Integrating the Best of Conventional and Complementary Approaches to Cancer, a full chapter was devoted to macrobiotics. [46]

It is challenging to define this diet exactly; there is great variability to what followers consume. We might describe it as an attempt to follow a ‘traditional Japanese diet’ or at least what Ohsawa imagined a traditional diet was while he lived in Paris. Leaving all philosophies aside, the macrobiotic diet from a macronutrient perspective can be described as a high complex carbohydrate, low fat diet. In a 1988 survey of 50 people consuming a macrobiotic diet, total fat intake averaged 23% of energy and total carbohydrate intake averaged 65% of energy. [47]Saturated fat intake accounted for only 4.5% of energy, while polyunsaturated fat intake, averaged 7.1% of energy.

Organically grown and minimally processed foods are encouraged. The diet consists mostly of whole cereal grains, including brown rice, barley, millet, oats, wheat, corn, rye, buckwheat and other less common grains and products made from them such as noodles, pasta and bread. These grains make up 40-60% of the weight of the diet. [48]

Vegetables, preferably locally grown, make up an additional 20–30% of the weight of the diet. An additional 5–10% of the diet’s weight comes from beans, including azuki, chickpeas and lentils; bean products such as tofu, tempeh or natto. Sea vegetables are consumed regularly, cooked with beans or as separate dishes. Fruits, white meat fish, seeds and nuts are eaten only occasionally. Those following macrobiotic diets avoid meat, poultry, animal fats including lard or butter, eggs, dairy products, refined sugars and foods containing artificial sweeteners or other chemical additives. [49]

The way this diet is described by percentage of total weight makes comparison with other diets, that are routinely described by macronutrient contributions by percentages, challenging.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/131.11.3056S

In recent years, assessments of the macrobiotic diet have been less harsh and potential anti-inflammatory actions have been suggested. A 2015 study suggested that following a macrobiotic diet might have superior anti-inflammatory potential than a standard American diet. [50] The diet is high in soy foods and this aspect may impact certain types of cancer in particular breast cancer.[51]

For all the enthusiasm about the macrobiotic diet over the past decades, there is still little research to suggest following the diet changes cancer prognosis. We cannot quote any clinical trials that report following the diet changes prognostic markers such as cancer free survival or overall survival.

Vegan Diet:

Donald Watson, a co-founder of the Vegan Society of England, is given credit for originating the term Vegan in 1944. Initially it meant a non-dairy consuming vegetarian. The Society expanded the definition in 1951 to mean, “the doctrine that man should live without exploiting animals”.

A vegan diet simply proscribes avoidance of all animal products such as meat, fish, eggs, dairy products and honey. Contrast this with a “Plant Based Diet” that suggests consuming only small quantities of these vegan-prohibited foods.

[Fyi, the abolitionist Fanny Kemble is given credit for first using the term vegetarian in print in 1839.]

Many famous personages have advocated meatless diets including the Greek mathematician Pythagoras, the British poet Percy Shelley, The American minister Sylvester Graham of graham cracker fame, and Louisa May Alcott’s father Amos.

Until recently vegan diets were adopted on ethical or philosophical grounds that focused on animal welfare. Only recently have ecological and health promoting arguments come to the forefront as the diet avoids meat which is linked to cancer and heart disease and greater greenhouse gas production. While following a vegan diet may increase consumption of cancer fighting foods, nothing in the ‘rulebook’ specifies what to eat. Being a vegan is all a matter of what one avoids.

Vegan dietary patterns can probably be traced back to the Jain religion, what is likely the oldest practiced religion. Rishabhdev, the first Tirthankar, is mentioned in Rig Veda, the oldest scripture of Hinduism believed to be at least 5000 years old. The last of the 24 Tirthankars of this cycle of time was Lord Mahavira. Jainism became prominent religion in India at the time of Mahavira, who was born in about 600 B.C. in present day Bihar. Central to Jainism is the practice of Ahimsa (non-violence) and this has been interpreted into an extreme form of vegetarianism. Practitioners of other religions also adopted vegetarianism over the centuries. Vegetarianism has been more widely adopted among upper caste Hindus and so distinguishing the effect of dietary patterns from the impact of socioeconomics is a challenge. About 20% of Indians are actually vegetarians. A third of the upper caste Indians are vegetarian. The government data shows that vegetarian households have higher income and consumption – are more affluent than meat-eating households. A third of the upper caste Indians are vegetarian The lower castes, Dalits (formerly known as untouchables) and tribes-people are mainly meat eaters.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-43581122

Data from India allows comparison of the impact vegetarian and non-vegetarian diets have on various health outcomes so let’s consider the Indian research specifically first.

Vegetarians in India have a higher standard of living as mentioned and are less likely to smoke drink alcohol and were less physically active. The have lower levels of cholesterol, lower triglycerides, lower blood pressure (systolic and diastolic), and lower fasting blood glucose compared to non-vegetarians.[52] The major risks for heart disease in India are not whether someone is a vegetarian or not but rather whether they smoke and how much fat they consume, both of which increase oxidative stress. [53]

In a large study published in 2014, the type of vegetarian diet played a significant role in risk of diabetes. This study evaluated data from 56,317 adults aged 20-49 years. Pesco-vegetarians and vegans had the lowest BMIs while lacto-ovo-vegetarians and lacto-vegetarians had the highest BMI among these non-meat eating groups. Diabetes incidence was lowest [0.9% (95% CI: 0.8-1.1)] among people consuming lacto-vegetarian, lacto-ovo vegetarian and semi-vegetarian diets and was highest in those consuming a pesco-vegetarian diet (1.4%; 95% CI:1.0-2.0).

Consumption of a lacto-, lacto-ovo and semi-vegetarian diet was associated with a lower likelihood of diabetes than a non-vegetarian diet.[54]

Several studies have considered the association between vegetarian diet and breast cancer risk and reached differing conclusions.

A 2017 multi-centre case control study on lifelong vegetarians concluded, that “…a vegetarian diet appears to have little, if any effect on the risk of breast cancer.”[55]

A 2018 multi-centre case control study in North India reached a different conclusion,

These researchers found that breast cancer risk was lower in lacto-ovo-vegetarians compared to both non-vegetarians and lacto-vegetarians with odds ratios of 0.6 (95% confidence intervals) (0.3⁻0.9) and 0.4 (0.3⁻0.7), respectively. They theorized that the difference between lacto-ovo-vegetarian and lacto-vegetarian dietary patterns could be due to egg-consumption patterns”[56]

These results agree with the results of an earlier 2013 study that, “… suggest[s] that non vegetarian diet is the important risk factor for Breast Cancer and the risk of Breast Cancer is more in educated women as compared with the illiterate women.”[57]

Other studies on vegetarian diets from India suggest not eating meat and fish lower risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. [58]Colorectal cancer trends higher in those with non-vegetarian diets [though a careful reading of the details got me to edit that to trends: Odds ratio of 1.5 (with a 95% CI of 0.3-8.7),]. [59]Risk of developing oral cancer is also higher among non-vegetarians but was greatly worsened by a regional habit of sleeping with a wad of chewing tobacco in the mouth. [60] A paper reports non-vegetarian diets also associated with tongue cancer but here again it is hard to break down the association of caste, illiteracy and non-vegetarian diet that might be linked to other factors such as smoking and chewing tobacco “Illiteracy and non-vegetarian diet proved to be a significant factor for [tongue cancer] patients only.”[61]

Considerable vegetarian research has come from other countries besides India. There is ample research suggesting benefit from following a vegan diet:

A meta-analysis by Dinu et al, published in 2017 that examined eighty-six cross-sectional studies and 10 prospective cohort studies reported that vegan diets were associated with a 15% reduction in risk of cancer. It is not clear that avoiding all animal products is necessary to see health benefit. Dinu’s bottom line is that vegetarian diets are associated with an 8% reduced risk in total cancer incidence.[62]

Dean Ornish has advocated vegan diets and used them in his trials treating prostate cancer. A low-fat vegan diet decreased PSA levels [63], lengthening telomeres [64], shifting gene expression, and improved quality of life measures.[65]In his trials, Ornish had patients follow a vegan diet, however, patients were also induced to exercise, take part in stress reduction activities, and experienced a high degree of social support, and adopted an almost religious zeal that the program was effective. This combination of factors challenges us to determine how much the diet itself contributed to results.

Looking at the data on colorectal cancer incidence from the famous Adventist Health Study-2, a prospective cohort study that included over 96,000 people, those who ate a vegetable-based diet with the addition of seafood had the lowest risk (43%; HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.40–0.82), while vegans and vegetarians had smaller risk reductions (19% and 18%, respectively) when compared with non-vegetarians.[66]

Dairy data is contradictory: high-fat dairy is associated with increased cancer mortality and risk of recurrence in prostate cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but dairy may protect against colorectal cancer. [67][68][69][70][71]

A large meta-analysis conducted by Italian researchers and published in 2017 looked at six cohorts totaling 686 629 individuals. “None of the analyses showed a significant association of vegetarian diet and a lower risk of either breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer compared to a non-vegetarian diet. By contrast, a lower risk of colorectal cancer was associated with a semi-vegetarian diet (RR = 0.86, 95% confidence interval = 0.79-0.94; I2 = 0%) and a pesco-vegetarian diet (RR = 0.67, 95% confidence interval = 0.53, 0.83; I2 = 0%) compared to a non-vegetarian diet.”[72]

A British study published in 2019 that followed members of the Epic-Oxford cohort for nearly 18 years tells us that compared with regular meat eaters (≥50 g per day: n = 15,181), the low meat eaters(<50 g of meat per day: n = 7615), fish eaters(ate no meat but consumed fish: n = 7092), and vegetarians (ate no meat or fish, including vegans: n = 15,426). were less likely to develop diabetes (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.63,95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54-0.75; HR = 0.47,95% CI 0.38-0.59; and HR = 0.63,95% CI 0.54-0.74, respectively). [Though I admit those numbers get complicated.]

Let’s try and sum that up simpler:

Compared to meat eaters, low meat eaters had a 27%lower risk of diabetes; the fish eaters had a 53%lower risk; and the vegetarians (who ate no meat or fish) along with the vegans, had a 37%lower risk. [73]This argues that a fish-eating vegetarian diet is superior to other variations on the theme at preventing diabetes.

Paleolithic Diet

Despite a name that suggests ancient origins, this diet strategy is the most recent of the dietary approaches discussed in this chapter. Over the years the Paleolithic diet has also been called the Stone Age, Caveman or Ancient Diet. It is a modern attempt to replicate a best guess of the diet of humans during the Paleolithic age before agriculture altered the food supply. It features foods that wereavailable to hunter-gatherers, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, meat, and eggs, while excluding grains, legumes, dairy products, and all processed foods. The concept of this diet originated in the 1970s, first promoted by Walter Voegtlin, a gastroenterologist who claimed thatreturning to an ancestral diet could sharply reduce incidences of Crohn’s disease, diabetes, obesity and indigestion, among other ailments. His ideas were summarized in his 1975 book, The Stone Age Diet. [74](that some have described as eccentric). Voegtlin starts his thesis with the assumption that humans were carnivorous until only about 10,000 years ago:

“Of course you are a human being! Everybody is.

But did you know that you are also an animal-a carnivorous animal? All humans are. Did anybody ever tell you that your ancestors were exclusively flesh-eaters for at least two and possibly twenty million years? Were you aware that ancestral man first departed slightly from a strictly carnivorous diet a mere ten thousand years ago? Well, he was and he did, and discussion of these salient points relevant to man’s diet will be the first task of this book. ” (The Caveman Diet, page 1)

Voegtlin’s assumption that Paleolithic diets were ‘strictly carnivorous’ is no longer believed correct.

In 1985, the New England Journal of Medicine published a paper written by S. Boyd Eaton, and Melvin Konner, titled “Paleolithic Nutrition: A Consideration of its Nature and Current Implications,” that argued intelligently that the human genome had evolved to eat foods that have been supplanted in the last hundred years that contribute to development of chronic diseases unknown in prior human generations. [75]

Eaton and Konner along with Marjorie Shostak further popularized the concept with their 1988 book,”The Paleolithic Prescription,”

The diet’s rationale is based on the idea—known as the “evolutionary discordance hypothesis”—that humans evolved for millennia with a relatively consistent diet, and that chronic diseases such as cancer arise from the consumption of foods available only after the agricultural revolution, which humans are not genetically equipped to digest. [76] The name “paleo diet” was coined by Loren Cordain, author of The Paleo Diet for Athletes, and a professor at Colorado State University in Fort Collins.

The modern Paleo diet reflects what the authors guessed actual Paleolithic people could have eaten. The diet is mainly meats and fish that prehistoric man might have hunted, and plants that might have been gathered, including nuts, seeds, vegetables and fruits. All grains and flours are avoided, as they are recent additions to the human diet. Dairy products are also avoided as these too are post paleolithic. Honey is the only sugar that’s allowed, as refined sugars also didn’t exist. Processed foods of any kind are not on the diet. These three prohibitions may be the only aspect of the diet that is true. Critics say we have little idea what the Paleolithic diet actually consisted of. It is not clear whether many paleolithic people really enjoyed the luxury of subsisting on fish and wild game. Some suggest it is more likely that people subsisted on seeds and insects. Still the basic list of modern foods to avoid (sugar, flour, and dairy products) is accepted by all.

In contrast to some other diets discussed in this review, (macro, alkaline, and ketogenic) there is published research including clinical trials on the Paleo diet including some studies that suggest following a Paleo style diet may have benefit in regard to cancer. While researchers have critiqued these studies as being ‘underpowered’ they nevertheless admit that they may be helpful, “… especially in weight loss and the correction of metabolic dysfunction.”[77][78][79] At least there is some published evidence to consider.

Some of the most interesting research on the Paleo diet comes from Kristine Whalen and colleagues who created a scoring mechanism to rank dietary pattern compliance for both Mediterranean and Paleo diets. In 2014, they reported that people at greatest compliance with either diet are at almost 30% lower risk of being diagnosed with colorectal adenomas.[80]In a 2016 study they reported that both of these diet scores are inversely associated with biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative damage. [81] The most striking findings to date were in their 2017 paper that compared these diet pattern scores to all cause and cause specific mortality. Those in the upper quintile of compliance to the Paleo diet were at a 23% lower risk of dying during the study while those most compliant with the Mediterranean diet were at a 37% lower risk of dying compared to those in the lowest quintile of compliance. [all-cause mortality were, respectively, 0.77 (95% CI: 0.67, 0.89; P-trend < 0.01) and 0.63 (95% CI: 0.54, 0.73; P-trend < 0.01).]. For cancer specific mortality closely following the Paleo diet was associated with a 28% lower risk while those Mediterranean adherents had a 36% lower risk. [82] While this study suggests following the Mediterranean diet has greater benefit, these data do suggest there is potential benefit from the Paleo diet, something we have yet to see demonstrated for these other diets. Given how much easier compliance is to a Mediterranean patterned diet than a Paleo diet, one has to question if it is thus reasonable to encourage the more challenging and possibly less effective strategy?

A paleo diet typically includes lean meats, fish, fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds — foods that in the past could be obtained by hunting and gathering. As mentioned, the paleo diet limits foods that became common when farming emerged about 10,000 years ago. These foods include dairy products, legumes and grains. [83]

Critics have found multiple reasons to question the Paleo diet’s basic assumptions based on current anthropologic evidence. There was no single Paleo diet. The foods people ate varied drastically by geographic location, season and other factors. While organized farming may have been a recent shift, grains have been harvested and consumed in Europe for 40,000 years. Humans do evolve to eat new foods as they are added to the diet. The ability to digest milk has been acquired by many people since cows were domesticated. Few foods still exist in anything close to an original state as agricultural practices and domestication have altered most foods. [84][85][86]

A last addition that some may find of interest:

A cost analysis published in April 2019 examined the monetary impact improving the American diet might have on healthcare costs. The study authors used the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) [1]that recommended 3 healthy eating patterns for predicting health outcomes. These patterns included the Healthy US-Style eating pattern as measured by the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) [2]or the Healthy Mediterranean Style eating pattern measured by a Mediterranean diet score (MED)[3]. Cost benefits were estimated for increasing the HEI and MED by 20% or increasing either to 80%. Increasing HEI and MED by 20% would reduce healthcare costs by $16.7 billion to $31.5 billion resulting from reductions in cardiovascular disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes for both patterns and including Alzheimer’s disease and hip fractures for the MED.

If US adults were to improve diet quality to achieve 80% of the maximum MED and HEI-2015 potential scores, cost savings were estimated at $88.2 billion and $55.1 billion, respectively. [87]

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4596721/

| Ketogenic | Alkaline | Macrobiotic | Paleo | Vegan |

| 60% fat | ? | 17% fat | ? | ? |

| 35% protein | 15% protein | |||

| 5-10% carb | 68% | |||

| 20-50 gm cho/day | 340 gm/day |

[1]DGA Guidelines https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/resources/2015-2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf

[2]https://www.fns.usda.gov/resource/healthy-eating-index-hei

[3]https://www.sevencountriesstudy.com/glossary2/mediterranean-diet-score/

Click to access RateYourMedDietScore.pdf

[1]Balter K, Moller E, Fondell E. The effect of dietary guidelines on cancer risk and mortality. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:90-102.

[2]Thomson CA, McCullough ML, Wertheim BC, et al. Nutrition and physical activity cancer prevention guidelines, cancer risk, and mortality in the women’s health initiative. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2014;7:42-53.

[3]Kabat GC, Matthews CE, Kamensky V, et al. Adherence to cancer prevention guidelines and cancer incidence, cancer mortality, and total mortality: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:558-69.

[4]Jankovic N, Geelen A, Winkels RM, et al. Adherence to the WCRF/AICR Dietary Recommendations for cancer prevention and risk of cancer in elderly from Europe and the United States: A meta-analysis within the CHANCES Project. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:136-44.

[5] Vergnaud AC, Romaguera D, Peeters PH, et al. Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research guidelines and risk of death in Europe: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Nutrition and Cancer cohort study1,4. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:1107-20.

[6]Bishop FL, Rea A, Lewith H, et al. Complementary medicine use by men with prostate cancer: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14:1-13

[7] Bishop FL, Prescott P, Chan YK, et al. Prevalence of complementary medicine use in pediatric cancer: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010;125:768-76.

[8] Sewitch MJ, Rajput Y. A literature review of complementary and alternative medicine use by colorectal cancer patients. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2010;16:52-6.

[9] Saghatchian M, Bihan C, Chenailler C, et al. Exploring frontiers: use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with early-stage breast cancer. Breast. 2014;23:279-85.

[10]Fouladbakhsh JM, Stommel M. Gender, symptom experience, and use of complementary and alternative medicine practices among cancer survivors in the U.S. cancer population. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:E7-e15.

[11]Woodyatt RT. (1921) Objects and method of diet adjustment in diabetics. Arch Intern Med 28:125–141.

[12]Wilder RM. (1921) The effect on ketonemia on the course of epilepsy. Mayo Clin Bull 2:307.

[13]Peterman MG. (1925) The ketogenic diet in epilepsy.JAMA 84:1979–1983.

[14]Atkins, R. Dr. Atkins Diet Revolution. Bantam Books. New York. 1972.

[15]Freeman JM, Kelly MT,Freeman JB. (1994) The epilepsy diet treatment: an introduction to the ketogenic diet. Demos, New York .

[16]D’Andrea Meira I, Romão TT, Pires do Prado HJ, et al. Ketogenic Diet and Epilepsy: What We Know So Far. Front Neurosci. 2019 Jan 29;13:5.

[17]Allen BG1, Bhatia SK2, Anderson CM, et al. Ketogenic diets as an adjuvant cancer therapy: History and potential mechanism. Redox Biol. 2014;2:963-70. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.08.002. Epub 2014 Aug 7.

[18]Chung HY1, Park YK2. Rationale, Feasibility and Acceptability of Ketogenic Diet for Cancer Treatment. J Cancer Prev. 2017 Sep;22(3):127-134.

[19]Allen BG1, Bhatia SK2, Anderson CM, et al. Ketogenic diets as an adjuvant cancer therapy: History and potential mechanism. Redox Biol. 2014;2:963-70. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.08.002. Epub 2014 Aug 7.

[20]Cell Metab. 2017 Feb 7;25(2):358-373. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.12.010. Epub 2017 Jan 12.

Prevention of Dietary-Fat-Fueled Ketogenesis Attenuates BRAF V600E Tumor Growth.

Xia S1, Lin R1, Jin L1, Zhao L1, Kang HB1, Pan Y1, Liu S1, Qian G1, Qian Z1, Konstantakou E1, Zhang B1, Dong JT1, Chung YR2, Abdel-Wahab O2, Merghoub T2, Zhou L3, Kudchadkar RR1, Lawson DH1, Khoury HJ1, Khuri FR1, Boise LH1, Lonial S1, Lee BH4, Pollack BP5, Arbiser JL5, Fan J6, Lei QY7, Chen J8.

[21]Weber DD, Aminazdeh-Gohari S, Kofler B. Ketogenic diet in cancer therapy Aging (Albany NY). 2018 Feb; 10(2): 164–165.

[22]Khodadadi S, Sobhani N, Mirshekar S, et al. Tumor Cells Growth and Survival Time with the Ketogenic Diet in Animal Models: A Systematic Review. Int J Prev Med. 2017 May 25;8:35.

Recently, interest in targeted cancer therapies via metabolic pathways has been renewed with the discovery that many tumors become dependent on glucose uptake during anaerobic glycolysis. Also the inability of ketone bodies metabolization due to various deficiencies in mitochondrial enzymes is the major metabolic changes discovered in malignant cells. Therefore, administration of a ketogenic diet (KD) which is based on high in fat and low in carbohydrates might inhibit tumor growth and provide a rationale for therapeutic strategies. So, we conducted this systematic review to assess the effects of KD on the tumor cells growth and survival time in animal studies. All databases were searched from inception to November 2015. We systematically searched the PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholars, Science Direct and Cochrane Library according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement. To assess the quality of included studies we used SYRCLE’s RoB tool. 268 articles were obtained from databases by primary search. Only 13 studies were eligible according to inclusion criteria. From included studies, 9 articles indicate that KD had a beneficial effect on tumor growth and survival time. Tumor types were included pancreatic, prostate, gastric, colon, brain, neuroblastoma and lung cancers. In conclusions, although studies in this field are rare and inconsistence, recent findings have demonstrated that KD can potentially inhibit the malignant cell growth and increase the survival time. Because of differences physiology between animals and humans, future studies in cancer patients treated with a KD are needed.

KEYWORDS:

Cancer; ketogenic diet; survival; tumor growth

PMID: 28584617 PMCID: PMC5450454 DOI: 10.4103/2008-7802.207035

Free PMC Article

[23]Sherman HC, Gettler AO. The balance of acid-forming and base-forming elements in foods, and its relation to ammonia metabolism. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1912;11:323-38.

[24]Montcourrier P, Silver I, Farnoud R, Bird I, Rochefort H. Breast cancer cells have a high capacity to acidify extracellular milieu by a dual mechanism. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1997 Jul;15(4):382-92.

[25]Wenzel U, Daniel H. Early and late apoptosis events in human transformed and non-transformed colonocytes are independent on intracellular acidification. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2004;14(1-2):65-76.

[26]Fenton TR, Lyon AW, Eliasziw M, Tough SC, Hanley DA. Meta-analysis of the effect of the acid-ash hypothesis of osteoporosis on calcium balance. J Bone Miner Res. 2009 Nov;24(11):1835-40.

[27]Fenton TR, Tough SC, Lyon AW, Eliasziw M, Hanley DA. Causal assessment of dietary acid load and bone disease: a systematic review & meta-analysis applying Hill’s epidemiologic criteria for causality. Nutr J. 2011 Apr 30;10:41.

[28]Fenton TR, Huang T. Systematic review of the association between dietary acid load, alkaline water and cancer. BMJ Open. 2016 Jun 13;6(6):e010438.

[29]Park YM, Steck SE, Fung TT, et al. Higher diet-dependent acid load is associated with risk of breast cancer: Findings from the sister study. Int J Cancer. 2019 Apr 15;144(8):1834-1843.

Dietary factors that contribute to chronic low-grade metabolic acidosis have been linked to breast cancer risk, but to date no epidemiologic study has examined diet-dependent acid load and breast cancer. We used data from 43,570 Sister Study participants who completed a validated food frequency questionnaire at enrollment (2003-2009) and satisfied eligibility criteria. The Potential Renal Acid Load (PRAL) score was used to estimate diet-dependent acid load. Higher scores reflect greater consumption of protein and phosphorus, and lower consumption of potassium, calcium and magnesium. The association between PRAL and breast cancer was evaluated using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression. We identified 1,614 invasive breast cancers diagnosed at least 1 year after enrollment (mean follow-up, 7.6 years). The highest PRAL quartile, reflecting greater acid-forming potential, was associated with increased risk of breast cancer (HRhighest vs. lowest quartile : 1.21 [95% CI, 1.04-1.41], ptrend = 0.04). The association was more pronounced for estrogen receptor (ER)-negative (HRhighest vs. lowest quartile : 1.67 [95% CI, 1.07-2.61], ptrend = 0.03) and triple-negative breast cancer (HRhighest vs. lowest quartile : 2.20 [95% CI, 1.23-3.95], ptrend = 0.02). Negative PRAL scores, representing consumption of alkaline diets, were associated with decreased risk of ER-negative and triple-negative breast cancer, compared to a PRAL score of 0 representing neutral pH. Higher diet-dependent acid load may be a risk factor for breast cancer while alkaline diets may be protective. Since PRAL scores are positively correlated with meat consumption and negatively correlated with fruit and vegetable intake, results also suggest that diets high in fruits and vegetables and low in meat may be protective against hormone receptor negative breast cancer.

© 2018 UICC.

[30]Kushi et al. (2001). The Macrobiotic Diet in Cancer. The Journal of Nutrition 131 (11): 3056S–3064S

Full text: https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/131/11/3056S/4686721

[31]Kotzsch, R.E. (1985) A corner of history: Hufeland. Macrobiotics Yesterday and Today Japan Publications New York, NY.

[32]Kushi et al. (2001). The Macrobiotic Diet in Cancer. The Journal of Nutrition 131 (11): 3056S–3064S

Full text: https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/131/11/3056S/4686721

[33]Kotzsch, R.E. (1985) A corner of history: Hufeland. Macrobiotics Yesterday and Today Japan Publications New York, NY.

[34]https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/131.11.3056S

[35]Sattilaro, A. J. & Monte, T. (1982) Recalled by Life: The Story of My Recovery from Cancer Houghton Mifflin Boston, MA.

[36]Kohler, J. C. & Kohler, M. A. (1979) Healing Miracles from Macrobiotics: A Diet for All Diseases. Parker Publishing West Nyack, NY.

[37]Kushi, M. & Jack, A. (1993) The Cancer Prevention Diet: Michio Kushi’s Macrobiotic Blueprint for the Prevention and Relief of Disease St. Martin’s Press New York, NY.

[38]Brown, V, Stayman, S. (1984) Macrobiotic Miracle: How a Vermont Family Overcame Cancer. Japan Publications New York, NY.

[39]Faulkner, H. (1993) Physician, Heal Thyself. One Peaceful World Press Becket, MA

[40]Nussbaum, E. (1992) Recovery from Cancer. Avery Publishing Group Garden City Park, NY.

[41]Schapira, D. V. & Wenzel, L. (1983) Florida CIS inquiries about unproven methods of cancer treatment and immunotherapy. Oncology Times June:12.

[42]Wells P. Macrobiotics: A Principle, Not a Diet

New York Times. JULY 19, 1978

[43]Zen Macrobiotic Diets. JAMA. 1971;218(3):397.

[44]U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment (1990) A corner of history: Unconventional Cancer Treatments, OTA-H-405. U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, DC.

[45]Cassileth BR, Lusk EJ, Strouse TB, Bodenheimer BJ. Contemporary unorthodox treatments in cancer medicine. A study of patients, treatments, and practitioners. Ann Intern Med. 1984 Jul;101(1):105-12.

Abstract

Public education, legislative action, and medical advances have failed to deter patients from seeking unorthodox treatments for cancer and other diseases. To study this phenomenon, we interviewed 304 cancer center inpatients and 356 patients under the care of unorthodox practitioners. A concomitant survey of unorthodox practitioners documented their backgrounds and practices. Eight percent of all patients studied never received any conventional therapy, and 54% of patients on conventional therapy also used unorthodox treatments. Forty percent of patients abandoned conventional care entirely after adopting alternative methods. Patients interviewed did not conform to the stereotype of poorly educated, end-stage patients who had exhausted conventional treatment. Practitioners also deviated from the traditional portrait: Of 138 unorthodox practitioners studied, 60% were physicians(M.D.s). Patients are attracted to therapeutic alternatives that reflect social emphasis on personal responsibility, pollution and nutrition, and that move away from perceived deficiencies in conventional medical care.

PMID:

[46]Lerner, M. (1994) Choices in Healing: Integrating the Best of Conventional and Complementary Approaches to Cancer MIT Press Cambridge, MA.

[47]Kushi, LH, Samonds K, Lacey JM, Brown, PT, Bergan JG, Sacks FM. The association of dietary fat with serum cholesterol in vegetarians: the effect of dietary assessment on the correlation coefficient. Am. J. Epidemiol. (1988) 128:1054–1064.

[48]Kushi M Jack A. The Cancer Prevention Diet: Michio Kushi’s Macrobiotic Blueprint for the Prevention and Relief of. (1993) St. Martin’s Press New York, NY.

[49]Kushi LH, Cunningham, Hebert JR, Lerman RH, Bandera EV, Teas J. The Macrobiotic Diet in Cancer. The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 131, Issue 11, November 2001, Pages 3056S–3064S.

[50]Harmon BE, Carter M, Hurley TG, Shivappa N, Teas J, Hébert JR. Nutrient Composition and Anti-inflammatory Potential of a Prescribed Macrobiotic Diet. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67(6):933-40.

Despite nutrient adequacy concerns, macrobiotic diets are practiced by many individuals with cancer and other life-threatening illnesses. This study compared the nutrient composition and inflammatory potential of a macrobiotic diet plan with national dietary recommendations and intakes from a nationally representative sample. Nutrient comparisons were made using the 1) macrobiotic dietplan outlined in the Kushi Institute’s Way to Health; 2) recommended dietary allowances (RDA); and 3) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2009-2010 data. Comparisons included application of the recently developed dietary inflammatory index (DII). Analyses focused on total calories, macronutrients, 28 micronutrients, and DII scores. Compared to NHANES data, the macrobiotic diet plan had a lower percentage of energy from fat, higher total dietary fiber, and higher amounts of most micronutrients. Nutrients often met or exceeded RDA recommendations, except for vitamin D, vitamin B12, and calcium. Based on DII scores, the macrobiotic diet was more anti-inflammatory compared to NHANES data (average scores of -1.88 and 1.00, respectively). Findings from this analysis of a macrobiotic diet plan indicate the potential for disease prevention and suggest the need for studies of real-world consumption as well as designing, implementing, and testing interventions based on the macrobiotic approach.

[51]Chi F, Wu R, Zeng YC, et al. Post-diagnosis soy food intake and breast cancer survival: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:2407-12.

[52]Shridhar K, Dhillon PK, Bowen L, et al. The association between a vegetarian diet and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors in India: the Indian Migration Study. PLoS One. 2014 Oct 24;9(10):e110586.

BACKGROUND:

Studies in the West have shown lower cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk among people taking a vegetarian diet, but these findings may be confounded and only a minority selects these diets. We evaluated the association between vegetarian diets (chosen by 35%) and CVD risk factors across four regions of India.

METHODS:

Study participants included urban migrants, their rural siblings and urban residents, of the Indian Migration Study from Lucknow, Nagpur, Hyderabad and Bangalore (n = 6555, mean age-40.9 yrs). Information on diet (validated interviewer-administered semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire), tobacco, alcohol, physical history, medical history, as well as blood pressure, fasting blood and anthropometric measurements were collected. Vegetarians ate no eggs, fish, poultry or meat. Using robust standard error multivariate linear regression models, we investigated the association of vegetarian diets with blood cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL), high density lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides, fasting blood glucose (FBG), systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

RESULTS:

Vegetarians (32.8% of the study population) did not differ from non-vegetarians with respect to age, use of smokeless tobacco, body mass index, and prevalence of diabetes or hypertension. Vegetarians had a higher standard of living and were less likely to smoke, drink alcohol (p<0.0001) and were less physically active (p = 0.04). In multivariate analysis, vegetarians had lower levels of total cholesterol (β = -0.1 mmol/L (95% CI: -0.03 to -0.2), p = 0.006), triglycerides (β = -0.05 mmol/L (95% CI: -0.007 to -0.01), p = 0.02), LDL (β = -0.06 mmol/L (95% CI: -0.005 to -0.1), p = 0.03) and lower DBP (β = -0.7 mmHg (95% CI: -1.2 to -0.07), p = 0.02). Vegetarians also had decreases in SBP (β = -0.9 mmHg (95% CI: -1.9 to 0.08), p = 0.07) and FBG level (β = -0.07 mmol/L (95% CI: -0.2 to 0.01), p = 0.09) when compared to non-vegetarians.

CONCLUSION:

We found beneficial association of vegetarian diet with cardiovascular risk factors compared to non-vegetarian diet.

[53]Kumar EP, Mukherjee R, Senthil R, Parasuraman S, Suresh B. Evaluation of oxidative stress and antioxidant status in patients with cardiovascular disease in rural populations of the nilgiris, South India. ISRN Pharmacol. 2012;2012:941068.

OBJECTIVE:

The objective of this work was to study the risk factors of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) in rural populations of the Nilgiris, south India, with stress on the various social habits and oxidant stress.

METHODS:

A total of 72 patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and 12 healthy volunteers were screened. Forty-seven patients with CVD (intervention group) and 10 healthy volunteers (control group) were randomly selected for the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants, and their demographic details were collected. A 6 mL blood sample was collected from each of the participants, and the serum was separated in the samples. The levels of enzymic (superoxide dismutase, catalase) and nonenzymic antioxidants (ascorbic acid) in the plasma were determined biochemically. The level of thiobarbituric acid species (TBARS), which is a predictor of lipid peroxidation, was measured.

RESULTS:

The participants of the study were stratified as according to demographic and social variables. The values of all the antioxidants and TBARS were statistically compared. Significantly reduced antioxidant levels and increased TBARS levels were found in the intervention group compared with the control group. The results suggest that the lowered antioxidant level may be a result of the oxidant stress of the disease. Statistically significant differences were not found in the antioxidant and TBARS levels when comparing smokers versus nonsmokers, alcoholics versus nonalcoholics, and vegetarians versus nonvegetarians.

CONCLUSION:

The major causes of CVD amongst the rural populations of the Nilgiris, south India, are preventable causes such as smoking and high fat intake, all of which cause oxidative stress, as seen in our study through various serum markers.

[54]Agrawal S, Millett CJ, Dhillon PK, Subramanian SV, Ebrahim S. Type of vegetarian diet, obesity and diabetes in adult Indian population. Nutr J. 2014 Sep 5;13:89.

BACKGROUND:

To investigate the prevalence of obesity and diabetes among adult men and women in India consuming different types of vegetarian diets compared with those consuming non-vegetarian diets.

METHODS:

We used cross-sectional data of 156,317 adults aged 20-49 years who participated in India’s third National Family Health Survey (2005-06). Association between types of vegetarian diet (vegan, lacto-vegetarian, lacto-ovo vegetarian, pesco-vegetarian, semi-vegetarian and non-vegetarian) and self-reported diabetes status and measured body mass index (BMI) were estimated using multivariable logistic regression adjusting for age, gender, education, household wealth, rural/urban residence, religion, caste, smoking, alcohol use, and television watching.

RESULTS:

Mean BMI was lowest in pesco-vegetarians (20.3 kg/m2) and vegans (20.5 kg/m2) and highest in lacto-ovo vegetarian(21.0 kg/m2) and lacto-vegetarian (21.2 kg/m2) diets. Prevalence of diabetes varied from 0.9% (95% CI: 0.8-1.1) in person consuming lacto-vegetarian, lacto-ovo vegetarian (95% CI:0.6-1.3) and semi-vegetarian (95% CI:0.7-1.1) diets and was highest in those persons consuming a pesco-vegetarian diet (1.4%; 95% CI:1.0-2.0). Consumption of a lacto- (OR:0.67;95% CI:0.58-0.76;p < 0.01), lacto-ovo (OR:0.70; 95% CI:0.51-0.96;p = 0.03) and semi-vegetarian (OR:0.77; 95% CI:0.60-0.98; p = 0.03) diet was associated with a lower likelihood of diabetes than a non-vegetarian diet in the adjusted analyses.

CONCLUSIONS:

In this large, nationally representative sample of Indian adults, lacto-, lacto-ovo and semi-vegetarian diets were associated with a lower likelihood of diabetes. These findings may assist in the development of interventions to address the growing burden of overweight/obesity and diabetes in Indian population. However, prospective studies with better measures of dietary intake and clinical measures of diabetes are needed to clarify this relationship.

[55]Gathani T, Barnes I, Ali R, et al. Lifelong vegetarianism and breast cancer risk: a large multicentre case control study in India. BMC Womens Health. 2017 Jan 18;17(1):6.

Author information

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The lower incidence of breast cancer in Asian populations where the intake of animal products is lower than that of Western populations has led some to suggest that a vegetarian diet might reduce breast cancer risk.

METHODS:

Between 2011 and 2014 we conducted a multicentre hospital based case-control study in eight cancer centres in India. Eligible cases were women aged 30-70 years, with newly diagnosed invasive breast cancer (ICD10 C50). Controls were frequency matched to the cases by age and region of residence and chosen from the accompanying attendants of the patients with cancer or those patients in the general hospital without cancer. Information about dietary, lifestyle, reproductive and socio-demographic factors were collected using an interviewer administered structured questionnaire. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals for the risk of breast cancer in relation to lifelong vegetarianism, adjusting for known risk factors for the disease.

RESULTS:

The study included 2101 cases and 2255 controls. The mean age at recruitment was similar in cases (49.7 years (SE 9.7)) and controls (49.8 years (SE 9.1)). About a quarter of the population were lifelong vegetarians and the rates varied significantly by region. On multivariate analysis, with adjustment for known risk factors for the disease, the risk of breast cancer was not decreased in lifelong vegetarians (OR 1.09 (95% CI 0.93-1.29)).

CONCLUSIONS:

Lifelong exposure to a vegetarian diet appears to have little, if any effect on the risk of breast cancer.

[56]Shridhar K, Singh G2, Dey S, et al. Dietary Patterns and Breast Cancer Risk: A Multi-Centre Case Control Study among North Indian Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Sep 6;15(9). pii: E1946.

Evidence from India, a country with unique and distinct food intake patterns often characterized by lifelong adherence, may offer important insight into the role of diet in breast cancer etiology. We evaluated the association between Indian dietary patterns and breast cancer risk in a multi-centre case-control study conducted in the North Indian states of Punjab and Haryana. Eligible cases were women 30⁻69 years of age, with newly diagnosed, biopsy-confirmed breast cancer recruited from hospitals or population-based cancerregistries. Controls (hospital- or population-based) were frequency matched to the cases on age and region (Punjab or Haryana). Information about diet, lifestyle, reproductive and socio-demographic factors was collected using a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire. All participants were characterized as non-vegetarians, lacto-vegetarians (those who consumed no animal products except dairy) or lacto-ovo-vegetarians (persons whose diet also included eggs). The study population included 400 breast cancer cases and 354 controls. Most (62%) were lacto-ovo-vegetarians. Breast cancer risk was lower in lacto-ovo-vegetarians compared to both non-vegetarians and lacto-vegetarians with odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) of 0.6 (0.3⁻0.9) and 0.4 (0.3⁻0.7), respectively. The unexpected difference between lacto-ovo-vegetarian and lacto-vegetarian dietary patterns could be due to egg-consumption patterns which requires confirmation and further investigation.

[57]Kamath R, Mahajan KS, Ashok L, Sanal TS. A study on risk factors of breast cancer among patients attending the tertiary care hospital, in udupi district. Indian J Community Med. 2013 Apr;38(2):95-9.

BACKGROUND:

Cancer has become one of the ten leading causes of death in India. Breast cancer is the most common diagnosed malignancy in India, it ranks second to cervical cancer. An increasing trend in incidence is reported from various registries of national cancer registry project and now India is a country with largest estimated number of breast cancer deaths worldwide.

AIM:

To study the factors associated with breast cancer.

OBJECTIVES:

To study the association between breast cancer and selected exposure variables and to identify risk factors for breast cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A hospital based Case control study was conducted at Shirdi Sai Baba Cancer Hospital and Research Center, Manipal, Udupi District.

RESULTS:

Total 188 participants were included in the study, 94 cases and 94 controls. All the study participants were between 25 to 69 years of age group. The cases and controls were matched by ± 2 years age range. Non vegetarian diet was one of the important risk factors (OR 2.80, CI 1.15-6.81). More than 7 to 12 years of education (OR 4.84 CI 1.51-15.46) had 4.84 times risk of breast cancer as compared with illiterate women.

CONCLUSION:

The study suggests that non vegetarian diet is the important risk factor for Breast Cancer and the risk of Breast Canceris more in educated women as compared with the illiterate women.

LIMITATION:

This is a Hospital based study so generalisability of the findings could be limited.

KEYWORDS:

Breast cancer; abortion; diet; menarche; risk factors

[58]Singh SP, Singh A, Misra D, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Indians: A Case-Control Study. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2015 Dec;5(4):295-302.

Abstract

BACKGROUND/AIMS:

NAFLD has today emerged as the leading cause of liver disorder. There is scanty data on risk factors associated with NAFLD emanating from India. The present study was conducted to identify the risk factors associated with NAFLD.

METHODS:

464 consecutive NAFLD patients and 181 control patients were subjected to detailed questionnaire regarding their lifestyle and dietary risk factors. Anthropometric measurements were obtained and biochemical assays were done. Comparison of different variables was made between NAFLD patients and controls using principal component analysis (PCA).

RESULTS:

NAFLD patients had higher BMI [26.25 ± 3.80 vs 21.46 ± 3.08 kg/m(2), P = 0.000], waist-hip ratio [0.96 ± 0.12 vs 0.90 ± 0.08, P = 0.000] and waist-height ratio [0.57 ± 0.09 vs 0.50 ± 0.06, P = 0.000] compared to controls. Fasting blood sugar [101.88 ± 31.57 vs 90.87 ± 10.74 mg/dl] and triglyceride levels [196.16 ± 102.66 vs 133.20 ± 58.37 mg/dl] were significantly higher in NAFLD group. HOMA-IR was also higher in NAFLD group [2.53 ± 2.57 vs 1.16 ± 0.58, P = 0.000]. Majority (90.2%) of NAFLD patients were sedentary. Family history of metabolic syndrome (MS) was positively correlated with NAFLD. Dietary risk factors associated with NAFLD were non-vegetarian diet [35% vs 23%, P = 0.002], fried food [35% vs 9%, P = 0.000], spicy foods [51% vs 15%, P = 0.001] and tea [55% vs 39%, P = 0.001]. Diabetes, hypertension, snoring and sleep apnoea syndrome were common factors in NAFLD. On multivariate PCA, waist/height ratio and BMI were significantly higher in the NAFLD patients.

CONCLUSION:

The risk factors associated with NAFLD are sedentary lifestyle, obesity family history of MS, consumption of meat/fish, spicy foods, fried foods and tea. Other risk factors associated with NAFLD included snoring and MS.

KEYWORDS:

ALT, Alanine Transaminase; AST, Aspartate Transaminase; BMI, Body Mass Index; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HC, hip circumference; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HOMA, Homeostatic Model Assessment; HOMA-B, beta-cell function; IR, insulin resistance; MS, Metabolic syndrome; NAFLD, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; PCA, Principal Component Analysis; SD, standard deviation; WC, waist circumference; anthropometry; diet; fatty liver; lifestyle; metabolic syndrome

[59]Bhattacharya S, Bhattacharya S, Basu R, Bera P, Halder A. Colorectal cancer: a study of risk factors in a tertiary care hospital of north bengal. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014 Nov;8(11):FC08-10.

AIM:

Age, sex, living place (urban or rural), smoking, alcohol consumption, dietary pattern, obesity are considered as risk factors for Colorectal cancer. Our study was done to evaluate the association between these risk factors and colorectal cancer in the population of North Bengal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The present study was done over a period of one year as a hospital-based analytical observational type of study with cross-sectional type of study design. All the patients undergoing colorectal endoscopic biopsy at the Department of Surgery, NBMC&H during the study period for various clinical indications comprised the study population. History and clinical examination were done of the patients whose colorectal biopsy were taken and filled-up in a pre-designed pre-tested proforma. Significance was tested at 95% confidence interval.

RESULTS:

There is an increased risk of colorectal carcinoma (CRC) with increasing age in our study population. Odd’s ratio for last 2 age groups are statistically significant with 2.83 for 41-50 years age group (95% CI is0.3-24), 13.6 for 51-60 years age group (95% CI is 2.1-85.9), 42.5 for more than 60 y age group patients (95% CI is 3.1-571). There is increased risk of colorectal carcinoma in males with an Odd’s ratio of 1.6 (95% CI is 0.5-5.5), but it is not statistically significant. There was an increased urban incidence of colorectal carcinoma compared to rural population with an Odd’s ratio of 1.8 (with a 95% CI of 0.6-5.9). In our study smoking also proved to be a risk factor and it is significant with an Odd’s ratio of 5.4 with a 95% CI of 1.6-8.7. Odd’s ratio for cases of alcohol consumption was 3.5 with a 95% CI of 1-11.6. Carcinoma cases were more common among patients with history of non-vegetarian dietary intake with Odds ratio of 1.5 (with a 95% CI of 0.3-8.7), but it was not statistically significant.Obesity has got a significant association with CRC in our study with an Odd’s ratio of 7.2 (with 95% CI of 1.3-40.2).

CONCLUSION:

More than 50 years of age, smoking, obesity were significant risk factors in our study. Other risk factors were though not significant, but much more common in colorectal cancer patients compared to non-malignant population.

[60]Gangane N, Chawla S, Anshu, Gupta SS, Sharma SM. Reassessment of risk factors for oral cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007 Apr-Jun;8(2):243-8.

A total of 140 cases of histologically confirmed oral cancer were evaluated for their demographic details, dietary habits and addiction to tobacco and alcohol using a pre-designed structured questionnaire at the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sevagram in Central India. These cases were matched with three sets of age and sex matched controls. Oral cancer was predominant in the age group of 50-59 years. Individuals on a non-vegetarian diet appeared to be at greater risk of developing oral cancer. Cases were habituated to consuming hot beverages more frequently and milk less frequently than controls. Consumption of ghutka, a granular form of chewable tobacco and areca nut, was significantly associated with oral cancer cases. Cases had been using oral tobacco for longer duration than controls, and were habituated to sleeping with tobacco quid in their mouth. Most cases were also addicted to smoking tobacco and alcohol consumption. Bidi (a crude cigarette) smoking was most commonly associated with oral cancer. On stratified analysis, a combination of regular smoking and oral tobacco use, as well as a combination of regular alcohol intake and oral tobacco use were significantly associated with oral cancer cases. Synergistic effects of all three or even two of the risk factors – oral tobacco use, smoking and alcohol consumption- was more commonly seen in cases when compared to controls.

[61]Rao DN, Desai PB. Risk assessment of tobacco, alcohol and diet in cancers of base tongue and oral tongue–a case control study. Indian J Cancer. 1998 Jun;35(2):65-72.

This is a retrospective case-control study of male tongue cancer patients seen at Tata memorial Hospital, Bombay, during the years 1980-84. The purpose of the study was to identify the association of tobacco, alcohol, diet and literacy status with respect to cancers of two sub sites of tongue namely anterior portion of the tongue (AT) (ICD 1411-1414) and base of the tongue (BT) (ICD 1410). There were 142 male AT patients and 495 BT patients interviewed during the period. 635 interviewed male patients who were free of any disease were considered as control. Bidi smoking was found to be a significant risk factor for BT patients and tobacco chewing for AT patients respectively. Alcohol drinkers showed about 45% to 79% excess risk for both sites of tongue cancer. Illiteracy and non vegetarian diet proved to be a significant factor for AT patients only. The study brings out that the location of cancer has got a direct bearing with the type of tobacco use and other related habits and this inturn may provide meaningful interpretation of variations observed in the incidence of tongue cancer around the world.

PMID: 9849026

[Indexed for MEDLINE]

[62]Dinu M, Abbate R, Gensini GF, et al. Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:3640-9.

[63]Ornish D, Weidner G, Fair WR, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes may affect the progression of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2005;174:1065-9; discussion 9-70.

[64]Ornish D, Lin J, Chan JM, et al. Effect of comprehensive lifestyle changes on telomerase activity and telomere length in men with biopsy-proven low-risk prostate cancer: 5-year follow-up of a descriptive pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1112-20

[65]Ornish D, Magbanua MJ, Weidner G, et al. Changes in prostate gene expression in men undergoing an intensive nutrition and lifestyle intervention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8369-74.

[66] Orlich MJ, Singh PN, Sabate J, et al. Vegetarian dietary patterns and the risk of colorectal cancers. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:767-76.

[67]Vieira AR, Abar L, Chan DSM, et al. Foods and beverages and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies, an update of the evidence of the WCRF-AICR Continuous Update Project. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1788-802.

[68]Aune D, Lau R, Chan DS, et al. Dairy products and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:37-45.

[69]Lu W, Chen H, Niu Y, et al. Dairy products intake and cancer mortality risk: a meta-analysis of 11 population-based cohort studies. Nutr J. 2016;15:91.

[70] Tat D, Kenfield SA, Cowan JE, et al. Milk and other dairy foods in relation to prostate cancer recurrence: Data from the cancer of the prostate strategic urologic research endeavor (CaPSURE). Prostate. 2018;78:32-9.

[71]Wang J, Li X, Zhang D. Dairy Product Consumption and Risk of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2016;8:120.

[72]Godos J, Bella F, Sciacca S, Galvano F, Grosso G. Vegetarianism and breast, colorectal and prostate cancer risk: an overview and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017 Jun;30(3):349-359.

Vegetarian diets may be associated with certain benefits toward human health, although current evidence is scarce and contrasting. In the present study, a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies was performed with respect to the association between vegetarian diets and breast, colorectal and prostate cancer risk.

METHODS:

Studies were systematically searched in Pubmed and EMBASE electronic databases. Eligible studies had a prospective design and compared vegetarian, semi- and pesco-vegetarian diets with a non-vegetarian diet. Random-effects models were applied to calculate relative risks (RRs) of cancer between diets. Statistical heterogeneity and publication bias were explored.

RESULTS:

A total of nine studies were included in the meta-analysis. Studies were conducted on six cohorts accounting for 686 629 individuals, and 3441, 4062 and 1935 cases of breast, colorectal and prostate cancer, respectively. None of the analyses showed a significant association of vegetarian diet and a lower risk of either breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer compared to a non-vegetarian diet. By contrast, a lower risk of colorectal cancer was associated with a semi-vegetarian diet (RR = 0.86, 95% confidence interval = 0.79-0.94; I2 = 0%, Pheterogeneity = 0.82) and a pesco-vegetarian diet (RR = 0.67, 95% confidence interval = 0.53, 0.83; I2 = 0%, Pheterogeneity = 0.46) compared to a non-vegetarian diet. The subgroup analysis by cancer localisation showed no differences in summary risk estimates between colon and rectal cancer.

CONCLUSIONS: